Michael Calderone at Politico has done yeoman's work describing recent exchanges between left-leaning politicians and right-leaning radio talk show hosts on the Fairness Doctrine. Their bantering may be a tale of sound and fury, whipping up audiences, signifying nothing, as Calderone suggests, but I will treat the threats of a new fairness doctrine as if the speakers delivered them seriously because it provides the opportunity to introduce excellent scholarly work on the subject.

Over the past several weeks, there has been a drum beat of Democratic politicians calling for more balance on the airwaves, or the implementation of a modern fairness doctrine. Calderone quoted Senator Debbie Stabenow [1], Senator Tom Harkin [2], and former President Bill Clinton [3] as supporting some type of Fairness Doctrine. Right wing talkers have vowed to fight the imposition of anything resembling political control over speech.

In the Public Interest, Hazlett [4] presents a brief history of broadcasting and its regulation. Broadcasting began in the U.S. in 1920. Spectrum assignment was based on first-come, first-served basis. In 1927, Congress and the Coolidge administration nationalized the spectrum out of what Hazlett described as, "mostly fear of private solutions to the spectrum-assignment problem." And thus political interference in broadcast speech began. Hazlett writes,

Instead of selling broadcast-spectrum rights, Congress and the FCC chose to assign them without dollar payment, while using the assignment power to help friends, punish enemies, and promote favored socioeconomic views.

The Federal Communication Commission, (FCC) which would eventually administer and enforce the Fairness, was created in 1934 to manage access to the airwaves in the public interest through the licensure process. The Roosevelt administration quickly realized that licensing could be a mechanism to punish radio stations that expressed anti-New Deal views. The Truman administration attempted to restore some controversial programming through the Fairness Doctrine (FD). Hazlett writes,

The Fairness Doctrine was cooked up by the regulatory chefs at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1949. The Doctrine required radio and television licenses "to provide coverage of vitally important controversial issues of interest to the community...and...a reasonable opportunity for the presentation of contrasting viewpoints on such issues."

The Fairness Doctrine orwellianly clothed the naked political aggression of administrations seeking political gain in the public good of free speech. Hazlett and Sosa, in a Journal of Legal Studies article, explain the enforcement mechanism granted by the Fairness Doctrine.

Enforcement of the FD was triggered by a complaint filed by a private party alleging an FD violation. The Commission would then request that the licensee in question respond to the complaint. The process would occasionally lead to a formal hearing by the Commission, during which the licensee's programming choices would be scrutinized in great detail. Most typically, FD complaints were filed either at the time of license renewal or license transfer. The cost (to the licensee) associated with the FD complaint ranged from the legal and lobbying expense involved in responding to the initial accusation, to the award of free airtime to complainants. The most potent weapon the FCC wielded, the capacity to revoke a license or refuse renewal (or transfer) for an uncooperative licensee, was rarely used. Nonetheless, the threat of loss of license was a powerful motivation for dispute settlement as well as behavior modification (as an "electronic publisher") to avoid programming likely to provoke complaints in the first place.

In the two referenced papers, Hazlett, and Hazlett and Sosa provide non-exhaustive examples of abuses of the Fairness Doctrine. Abuse was bipartisan. The Eisenhower administration awarded television licenses to GOP businessmen. The Kennedy administration used the Fairness Doctrine through the Democratic National Committee (DNC) to stifle right-wing broadcasters who might oppose their nuclear test-ban treaty. The DNC during the Johnson administration harassed unfriendly stations. License harassment of unfriendly stations was a regular agenda item during the Nixon administration, and in one thirty day period, twenty-one presidential directives were issued to follow up on unfair news reporting.

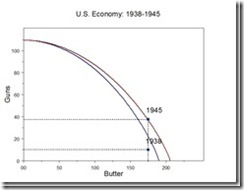

Hazlett and Sosa demonstrated the constraints that the Fairness Doctrine had on speech by measuring changes in radio programming before and after it was revoked by the FCC in 1987. The news, newstalk, and public-affairs radio format expanded from 7% of AM formats in 1987 to 28% in 1995; these formats expanded from 3% of FM formats in 1987 to 7% in 1995. Re-instating the Fairness Doctrine would lower the quality of programming, and, consequently, lower radio revenues. The real cost is the chilling impact on political speech, a cost that politicians from both parties who wish to reinstate the Fairness Doctrine understand.

[1] Michael Calderone, "Sen. Stabenow wants hearings on radio 'accountability'; talks fairness doctrine," Politico, February 5, 2009.

[2] Michael Calderone, "Sen. Harkin: 'We need the Fairness Doctrine back,'" Politico, February 11, 2009.

[3] Michael Calderone, "Clinton wants 'more balance' on airwaves," Politico, February 12, 2009.

[4] Hazlett, Thomas W. "The Fairness Doctrine and First Amendment," The Public Interest, Num. 96, Summer 1989.

Hazlett, Thomas W. and David W. Sosa. "Was the Fairness Doctrine a 'Chilling Effect'? Evidence from the Postderegulation Radio market," The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1, January 1997.

Read more!